This was a splendid walk along a pretty valley and across a moor full of fascintating lead mining history. As a bonus, it gave me the chance to visit the remains of a henge.

I hadn’t heard about the lead mining near Yarnbury on Grassington Moor until it was mentioned to me by fellow blogger the Mountain Coward. After my interesting walk around the remains of lead mining in Nidderdale, I was keen to do the Grassington Moor Lead Mining Trail that winds its way through these old workings. It’s possible to just drive to Yarnbury and walk the Trail from there, but I wanted to incorporate the Trail into a longer walk. I therefore decided to start my walk in the village of Hebden and follow the small valley of Hebden Beck up to the Trail. I also noticed that there is a henge marked on the map not far from Yarnbury, and I thought that I could incorporate a detour to this into a circular walk that came back over the hills above Wharfedale.

Hebden runs along a side valley of Wharfedale down which flows a small river. In the past, it had always been somewhere I’d driven through on the way to somewhere else rather than somewhere I stopped. I therefore enjoyed seeing this pretty village properly for the first time as I crossed over the busy B6265 to follow a quiet lane up the valley.

The road stayed close to Hebden Beck as it passed pastures criss-crossed with drystone walls. As the lane began to move from away the beck, I took a quick detour across a field and back to the stream to see the attractive Scale Haw Falls (AKA Scala Falls). I then returned the way I had come to carry on along the lane into Hole Bottom.

Despite its unpromising name, Hole Bottom is lovely. It’s a small collection of attractive, limestone cottages, including a terrace of neat holiday cottages. These sit on a rise near the Beck and in view of a rocky scar on the moor side across the valley.

There used to be a mill at Hole Bottom. The remains of this can be seen in a small weir in Hebden Beck and, just beyond the holiday cottages, a series of low walls and stone-paved floors by the river’s bank. I passed these as I headed to a stone bridge, which, like the road running up the valley, had been built by miners to enable access to the workings. I took this route as I carried on up the valley.

I enjoyed walking along this valley. The beck, woods, drystone walls, and fields are attractive. It’s also a varied route and full of interesting features such as tumbling-down crags and mining remnants. After a few minutes of walking along it, I came to a short section of drystone wall in which there was an archway into a dark tunnel into the hillside. A metal gate was bolted over this, and an adjacent Yorkshire Water sign stated that this was the “Hebden Ghyll; Lanshaw Level Intake”. It looked like an adit (i.e. a horizontal mining tunnel), and so I was puzzled by the sign describing it as a water intake. I was sufficiently intrigued to do an internet search when I got home, and found answers on a website devoted to the history of Hebden. This explains that this is an adit leading into Longshaw Level – a lead mine excavated in about 1863. The miners inadvertently hit a small stream, and the mining company decided to put the water to use by piping it down the valley to power the waterwheel in Hole Bottom. It went on to explain that by the early 1960s, Hebden’s rising population and a new, mains sewage system created a need for more water for the village. The Craven Water Board apparently decided this could come from this adit, and undertook construction work (including a water treatment plant) to put this into action. The Hebden history website states that there were complaints that the water piped to Hebden was excessively hard and in “the end it was deemed unwise to be pouring water from a lead mine down the throats of the locals…” This approach to supplying drinking water was therefore abandoned, and a mains supply was installed instead.

As I continued up the valley, I passed a waterfall pouring off the fell and lots of rabbits scurrying around.

The valley turned a corner and widened out to reveal the next mining level. After another gated adit, I came to a flattened, paved area by the side of the beck. There were the stumpy walls of ruined buildings, and spoil heaps were dotted around. This had been a dressing floor, where the bouse (raw materials brought up from the mine) was sorted into galena (lead ore) and unusable rock. It would have taken materials from the mines around Hebden Beck and Bolton Gill. The remains of an incline or track led up the side of the valley to the roofless shell of another stone building. I found this a strangely pretty place with its ruins and its spoil of brown and grey stones sat by a stream.

The track led on through a gate to taller spoil heaps at the junction of Hebden Beck and Bolton Gill. I dropped down to Hebden Beck and crossed it by some stepping stones. The grassy path then got progressively narrower and muddier, before I re-joined the track at a ford.

The track climbed past large spoil heaps, and then sloped down to the beck and a large lime kiln cut into the side of the valley. A short uphill zigzag brought me onto the moor and, a little while later, a junction with the Duke’s New Road. I took this grandly named track into another mining area and onto the Grassington Moor Lead Mining Trail.

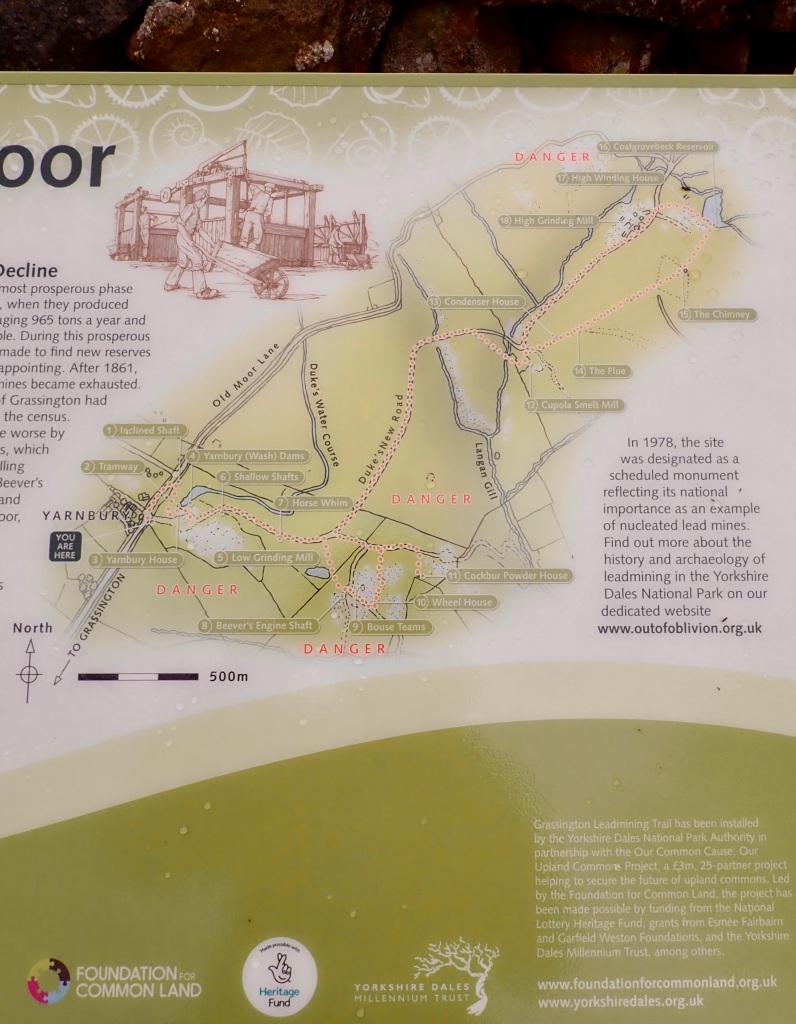

Mining on these moors can be traced back to 1604, when the 4th Earl of Cumberland built a smelt mill near Linton Church and began working the lead mines. The next few hundred years would see changes in the ownership of the mineral rights, the system under which miners worked the land, and the nature of production. From reading the information boards on the Mining Trail, it felt to me like a war of attrition between the miners, as they chased the veins of ore deeper, and the unrelenting water level of Yorkshire moorland that regularly impeded their progress. Improvements in drainage tunnels and advances in technology seemed to be the key to the miners’ success.

A surge in the application of such technology appears to have come after 1818, when the 6th Duke of Devonshire (who held the mineral rights at that time) appointed the renowned mining engineer John Taylor as his Mineral Agent. The improvements introduced by Taylor included a 15-metre diameter waterwheel to drive pumps in the Coalgrovebeck Mine, deep shafts accessed by ropes wound by horse-powered winding machines, centralised dressing floors, and new roads. These changes saw the mines enter their most productive period. Between 1821 and 1861, the mines produced 20,273 tonnes of lead and employed about 170 people. However, output steadily fell after this as the mines became exhausted. This reduction in output coincided with the price of British lead being kept down by rising, cheap imports. This resulted in work at the mines on Grassington Moor stopping in May 1880.

This turned out to not be the end, as there were efforts over the years to extract barytes, fluorspar, and lead from the spoilt heaps. The biggest such operations happened between 1916 and 1920, and between 1956 and 1963. 1918 also saw lead mining re-start, albeit only for a relatively short time.

The first of the mining relics I reached on the Grassington Moor Lead Mining Trail was the Cockbur Powder House. This is a sturdy, small, and modern-looking stone building that was used to store blasting powder. Unsurprisingly, this building sits on the edge of the site.

I then headed back to the Duke’s New Road, before taking another track into a moonscape of spoil heaps in which the ruins of a building were half-buried in a rocky dune.

This building had contained a waterwheel which had operated the pumps in the nearby workings, including the Beever’s Engine Shaft. This was sunk in 1836 to a depth of 91m. The entrances to this shaft sit in a bank behind the wheelhouse, and I clambered to the top of this to look through the metal grid covering the shaft. Strangely, I had the sense that the shaft was deep even though I could see little in the dark hole.

Via the Duke’s New Road, I then made my way across the moor and over a large dam that had been built across the stream. The New Road then headed up the slope of the moor to the remnants of the Cupola Smelt Mill. The construction of this smelt mill in 1792 was apparently a major development in the history of mining on the moor. Previously, peat and wood were used to fuel the hearths that heated the ore to obtain the valuable metal. These were replaced with two coal-burning reverberatory furnaces (these worked by keeping the ore kept separate from the burning fuel).

The Cupola Smelt Mill had intriguing arches and what looked like curved chimneys, but the best lead mining relic I saw on Grassington Moor was the long flue that ran from this mill to the tall chimney. This flue is an arched, stone tunnel covered by earth and grass. It appears as a long mound running up the moor, with periodic, arched openings and branches heading off in other directions.

The flue was used to maximise the amount of lead obtained from the ore. The smelting process resulted in particles of lead being carried away with the waste gases from the furnaces. This lead would condense on the flue’s walls. Washing out the flue would cause the lead to collect in settling ponds near the end of the flue, from where it could be recovered. I found it interesting that this process wasn’t started here until more than 60 years after the Cupola Smelt Mill was built.

I followed the flue to the imposing stone chimney and good views over the moors. A short walk from there took me to Coalgrovebeck Reservoir, which stored water for use at the High Grinding Mill and the High Winding House. This reed-edged small lake was a gorgeous location, with views over the other mine workings spread out into the distance. I felt tired, but happy to be there, as I took a faint path back to the track. I then headed across the moor to Yarnbury.

Yarnbury is a cluster of houses on a rough plateau on the edge of the mining area. I imagine that these buildings were once a large farm and/or were used by the mine operators. They now look like expensive homes. Next to the the rough lane that runs past Yarnbury is an impressive stone archway that is the entrance to an inclined shaft. This shaft goes under the lane and down to a depth of 37m, and was used as a means for horses to haul ore to the surface. This was my fascinating and last look at the mine workings as I left behind them to head over boggy fields to find Yarnbury Henge.

Yarnbury Henge dates from the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age. It sits in a roughly flat pasture with views across Wharfedale to the surrounding fells. The Henge consists of a low, roughly circular bank with a shallow, internal ditch, which acts to form a central platform. There is an entrance causeway to the South-East. The Henge is about 30m across and, unfortunately, has been slightly damaged by quarrying. Archaeological excavations have found fragments of pottery urns, burnt flint, charcoal, and cremated bone in the centre that suggest that it was used for cremations. A small, Neolithic, rectangular post and wattle house was also found by archaeology students in the same field in 2014.

It’s easy to get to Yarnbury Henge, as a public right of way runs past it. However, it would be easy to walk that right of way and not notice the Henge at all. It looks like a grassy mound from the side, and you really need to stand on its’ bank to get a sense of it. Yarnbury Henge isn’t visually dramatic history. I think that the awe and interest that it can inspire come from knowing it’s age, it’s role, and the significance it must have held for local people. I walked around the site for a while trying to appreciate it, before heading back over the fields to pick up my route back to Hebden.

This route took me down the hill through wet, muddy fields and along rough tracks. On the map this had looked like it might be a long traipse through farmland, but I enjoyed it a lot more than I thought I would. The views down Wharfedale expanded as I got lower into the dale, oystercatchers and curlews flew around, and ewes with new lambs gave me hard stares to warn me off getting too close. I eventually squelched through the last field and through a gate into Hebden.

Further information

A detailed history of lead mining in this area is available on the website of Historic England.

There is a short briefing on the Yarnbury Henge by The Prehistoric Society. For more detailed information, a copy of an academic paper reporting on the last archaeological examination of the Henge is available on the website of the University of Bradford.

Brilliant post – I thought you would go and have a look after I mentioned it but didn’t know you’d go so soon. You made a really good day of it and saw much more than I ever did up there. For instance, I must have walked past that henge across the fields but had no idea about its existence! Nor did I ever see the slanted adit for the horses.

You can actually go up the inside of the long flue to the tunnel (collapsed sections not withstanding) – you’d probably have to wear old clothes though (which I generally do when I’m out walking!)

We used to play cricket on a flat and fairly wide section of riverbank up Hebden Ghyll – me, my brother, Mum and Dad. Patrick Stewart the actor also used to own a property up the hillside above the start of the ghyll too apparently.

Thanks. I’m glad that you liked it.

Thank you also for suggesting it as somewhere to go. I’m not sure I would have come across it otherwise.

The henge and inclined shaft are both easy to miss. The way the inclined shaft goes under the lane means that you could mistake it for a bridge over a little stream or (very substantial) drain if you were walking past.

I did think about looking at the flue more closely, but decided that might be a full on and that my curiosity has limits.

I can see how there might be a good spot or two to play cricket there. It’s a lovely area.

You’ve got me curious now about which house Patrick Stewart owned.

From what I remember, Patrick Stewart’s house (which he probably no longer owns anyway) was high up the valley side on the right as you enter the gill from the village.

Actually, it’s worth googling Hebden Ghyll and Patrick Stewart – a few results for it

me again… Scar Top House

I Googled Scar Top House. There are media reports that Sir Patrick Stewart put the house on the market in 2016. The listing is still online at https://media.onthemarket.com/properties/2906255/doc_0_0.pdf and so you can see what the house looks like. It’s a lovely property and in a fantastic location. I’m a bit envious.

Thanks. I wouldn’t have known about it if you hadn’t mentioned it.

I’ve just been looking at the estate agent photos!

Is that really a dining area between the bathroom and wc on the first floor. Weird. Do you think they meant dressing area 😀

I think you’re probably right that it’s a typo/error on the plan in the listing.

Plus you’re a bit tall. Easier to send your son up with the camera instead.

Isn’t that a bit like sending him up a chimney?

There’s probably a drone on the market for that sort of exploring.

🙂

As you say ‘a splendid walk’. You write up full of information. Must try and get up there this summer.

Thank you.

It’s definitely worth a visit.

Looks like a great walk with a lot of interesting things to see and history.

Thanks Melodie.